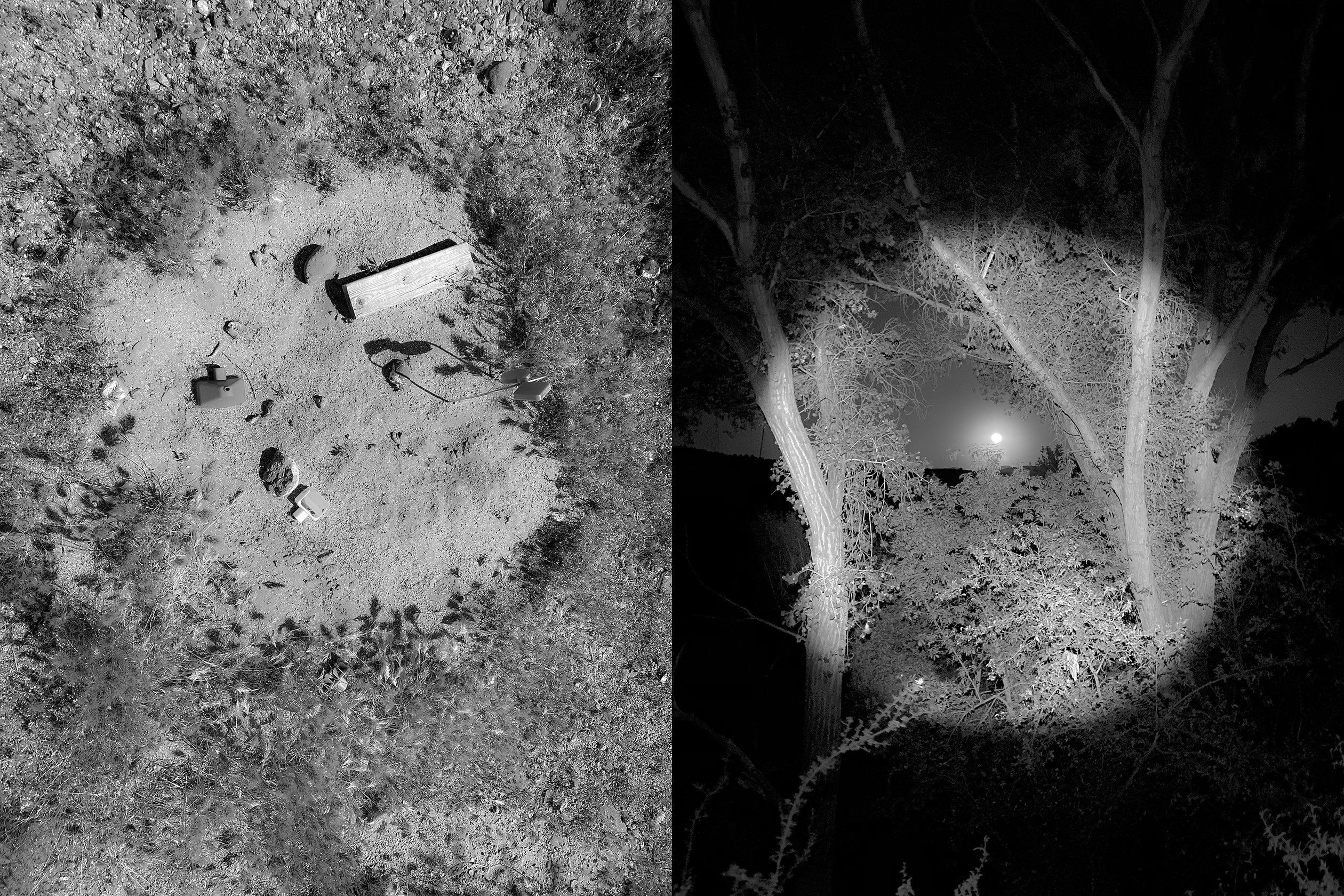

Hard to See

Hard to See

Ella Sweeney questions the place of fairy lore in the 21st century

Images and video by Reid Calvert

One day, during a period of extensive research into Irish folklore, the poet William Butler Yeats met a certain Mrs. Connolly who had the most incredible repertoire of fairy stories he had ever heard. Yeats sat listening to her stories, proverbs and lore well into the evening but as the night drew on, Yeats had to leave. As Mrs. Connolly stood at the door, Yeats turned back to ask her tentatively “Do you believe in fairies?” Mrs. Connolly threw back her head and laughed. “Oh, not at all Mr. Yeats, not at all.” Yeats turned away and slouched off down the path. As he did, Mrs. Connolly called after him, “but they’re there, Mr. Yeats, they really are there.” She was well aware that fairies don’t need human belief to be real. They don’t need us to believe in them to be there, just as things don’t need to be seen to exist.

If I caught a glimpse of a fairy what would l see? Near my hometown in Lancashire, I would probably see an angry shapeshifting Brag (hobgoblin) dressed in a ragged red hat and green clothing. He might quickly transform into a horse or donkey ready to buck any brave rider off. In the Scottish Highlands I might meet a Caoidheag (banshee), a weeping woman wrapped in the white cloth of mountain mist, warning of a coming death. In some areas of Ireland, I may be seduced and kidnapped by a Gean-cánach (love-talker), a humanoid fairy wandering the fields in his finest dress. But I hope that if I do ever meet one, I will see a fairy as described in Robert Herrick’s Description Of The King And Queene Of Fayries:

First a cobweb shirt, more thin

Than ever spider since could spin [….]

A rich waistcoat they did bring,

Made of the Trout-fly’s gilded wing […]

The outside of his doublet was

Made of the four-leaved, true-loved grass,

Changed into so fine a gloss,

With the oil of crispy moss […]

On every seam there was a lace

Drawn by the unctuous snail’s slow pace […]

About his neck a wreath of pearl,

Dropped from the eyes of some poor girl1

Everything that I know about fairy history comes from Oscar Wilde’s mother, Lady Francesca Speranza Wilde, and her book Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland written in 1887. It is a book written with respect for the fairy faith and honours the invisible, taking seriously what is truly hard to see. According to Lady Wilde all Irish legends, including the fairy, point to the East for their origins, not the North. “From the beautiful Eden-land at the head of the Persian Gulf, where creeds and culture rose to life, the first migrations emanated” including flocks of fairies from Iran to Ireland. According to Lady Wilde the Feadh-Ree (fairy) comes from the word Peri, a race of mythical Persian beings who flew about the Gulf.2

But this is as far as I can go in attempting to place the origin of the fairy. There are many things in the world that resist historicization – fairies are one of them. Often history (the kind in textbooks) attempts to conquer; it tries to calm the dead and the forgotten that still haunt the present, separating ‘us’ from ‘them’. History demands facts and rationality, neither of which fairies can provide. It accepts a popular perception of the past, but only under its own terms. Fairies do not abide by these terms because they withstand the very idea of fact. There is no concrete evidence of the fairy. No photo, no footprint, just stories.

Today, the fairy faith has been relegated to a thing of the past. Fairies no longer exist, or maybe they never did. Since the Scientific Revolution, through the Renaissance, up past the Enlightenment, well into the Industrial Revolution through to today, rationality and modernity have cemented themselves as the triumphant winners in a battle between what we can and cannot prove to be real. Myth and magic are no longer a part of modern everyday life, they persist only as anachronistic parts of culture: inspiration for bedtime stories and Disney films. What was once used as a sinister warning for children – the folk or fairy tale – has been watered down, their stories declawed and rolled out for mass entertainment.

Modernity, with the help of the Church and state, shored up power in the hands of the few and took root alongside the colonial project. Science and technology have been used as oppressive forces both on the working class in Europe and as an excuse to colonise; to claim and destroy cultures, people and land all in the name of ‘progress’. The British Government were releasing propaganda during the interwar period which glorified Britain’s occupation of India and many countries in Africa, claiming they were helping indigenous populations through industrialisation.3 This kind of mindset is not yet a memory, we can see it in the UK and US fixation with military occupation, where they claim they are doing so to implement democracy.

Words like sorcerer, barbarian, savage and infidel have been used to define ‘them’, the archaic other, against ‘us’, those of rational Western thought. Modernity has positioned itself against the past and established a global hierarchy, distinguishing Western Euro-America as the most advanced in a timeline which values ‘progress’. In an advanced, rational, scientific world, there is no use for magic, spirits or fairies. Our environment is no longer an accepted receptacle of mystical power and nature has become transformed into a universal system that has to be understood. Modernity has defined itself against its opposite. This opposition has to be destroyed, liberated or turned into a fetishistic object, examined and enjoyed by spectators.

In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, the sociologist Max Weber concludes that modernity has disenchanted the ‘West’ and science has defeated magic, religion and spirits and gods once and for all.4 Yet, religion and the God of Western Christianity have not simply disappeared, they have found their ‘proper’ place: faith is confined to the private sphere and God is confined to some faraway transcendent kingdom. A gaping hole has been left behind. Modernity has attempted to fill this gap with a distinctly modern faith. A faith in ‘progress’ to aid us in making sense of and finding meaning in dominant modern institutions: consumerism and freedom of the market along with bureaucratic machines and large media corporations. “Consumerism”, writes the German mystic Dorothee Soelle, “is the new religion”.5

But this notion of disenchantment, the stripping away of myth and magic, implies that those who have undergone this process are the only ones who have direct access to what is truly real. Disenchantment sets the ‘West’ up against the ‘Other’. In the end, the notion of disenchantment enacts exactly what it decries as it relies on an understanding of the non-Western and non-modern subject as someone who is unable to recognise what is real; who fundamentally cannot grasp reality. If this enchanted world is open and porous to gods, magic and spirits, it is confused.

But I prefer not to follow this tale of disenchantment. I don’t think we have to re-enchant ourselves in order to see, believe or trust that there is some truth to myths or tales. The fairies have always been there, vibrating under the surface, drifting through the cracks left behind by science, providing an explanation for things which are otherwise unexplainable. The traditional fairy faith may be on its way out but remnants of its magic still linger.

During the Victorian period, fairies underwent a transformation. Instead of being portrayed in their traditional form – a race of terrifying beings who should never be crossed – they became a softened and aestheticised myth. If modernity cannot destroy the non-rational other, it will eventually fetishise, and so the popular image of the fairy was co-opted. The popular image that we have today comes from literary and aesthetic fancies of eighteenth century poets and painters.

In Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, the anthropologist Talal Asad argues that much of the imagery and literature of nineteenth-century romanticism constituted a coming to terms with the modern secular world, of being enclosed within it and seeing no escape.6 The images of a pre-modern past or non-modern other acquired, only in retrospect, the attractive quality of otherworldly enchantment. Visions of tiny winged people – good, delicate, sparkly and beautiful – inhabit our modernised fairy tales.

But there is a peculiar contemporary resurgence in fairies. Aesthetic internet cultures such as cottagecore and fairycore have emerged straight out of a nineteenth-century fairytale book – they connote a return to the land, to a simple rural life filled with white cotton tablecloths, lace doilies and voluptuous spotted toadstools. Brothers Grimm with a sexual, Lolita twist. Then there is goblincore, a dirtier, grimier version of the above, where the hoarding of rocks, trinkets and dead bugs is revered as the pinnacle of cool.

Running parallel to all of this is something which can perhaps illuminate the aesthetic decisions made by these groups. Interest in folk culture seems to be becoming quite the trend. In particular, there’s been a noticeable spike in the popularity of Celtic traditions, including an emphasis on remembering and reviving the traditional fairy faith and documenting modern fairy encounters. Websites and podcasts such as Blúiríní Béaloidis and Cailleach’s Herbarium are full of traditional fairy stories and modern fairy encounters. But you won’t find anything resembling Tinkerbell here, these fairies are those of tales past: sinister and threatening characters who are up to no good.

It is worth remembering that the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland occurred against the backdrop of the Gaelic Revival, which began in the 19th century and went hand-in-hand with the fetishisation of the fairy. It was itself a resistance to modernisation, looking back to imagine another possible future. The movement grew from a cultural interest in the Celtic people, portraying Scottish, Irish and Welsh people inaccurately as noble savages, trapped in a past not unlike the one the cottagecore Instagrammer dreams of.

Any revitalised interest in fairies is an act of reclamation. But any act of cultural reclaiming sees the thing changed, morphed by both its historical and contemporary contexts. To borrow from the philosopher Isabelle Stengers writing on the resurgence of Neo-pagan witchcraft, modern perspective can be defined by a collective pride in the ability to interpret the supernatural in terms of its social, cultural and political contrasts: in being able to rationalise the unknown. But this “knowing better” means forgetting that many of us are heirs to brutal acts committed in the name of civilization and reason.7

So it is interesting that an aesthetic and cultural resurgence surrounding the fairy comes now, at a time of political and social tension. The modern industrial project is revealing itself to have been a disaster, capitalism does not work for the common good and science is unable to answer all of our questions. People, yet again, are resisting the tale of modern progress. From the Indigenous Environmental Network and Unitierra or Universidad la Tierra (University of the Earth) in Oaxaca Mexico and even to the Creation Care of Evangelical and Christian communities, people are recovering the land, spirits, beings and gods that modernity relegated to the sidelines. There they are finding what was once common belief and what remnants of this still linger.

Starhawk, a Neo-pagan witch, writer and activist, writes that to utter the word magic is already an act of magic: the word itself puts us to the test – how seriously will we take this word?8 The same could be said about fairies. We may never see one or be compromised by one, but confronted with the current reclaiming of fairy lore and aesthetics, perhaps we could learn something from this test. Won’t capitalism have won out forever if we are ready to submit ourselves to a disenchanted world, to close our eyes, sober our senses, have to see to believe?9 Maybe, then, the true trick of the fairies is their fabricated nature, their inability to be pinned down to any one aesthetic or experience; the undecidability that they confront us with.

What form the fairy comes in might change but they will remain in our cultural psyche. Fairies are nifty, they can’t be bound to the pages of history. The search for any evidence of them always ends up in some odd wasteland of rationality. However, amongst every pile of waste, there is dust – maybe even fairy dust. As the historian Carolyn Steedman describes, dust is opposite to waste, it whirls around and around collecting and hoarding as it goes.10 It is circularity, an impossibility of things ever truly being destroyed. Like dust, fairy history always ends where it started: in the cracks. Nothing just disappears, some things are just hard to see.

- Herrick, Robert & Steward, Simeon. A Description of the Kings [sic] of Fayries Clothes, brought to him on New-Yeares day in the morning, 1626, by his Queenes Chambermaids, A Description of the King and Queene of Fayries: Their Habit, Fare, their Abode, Pompe and State, 1635.

- Wilde, Lady Francesca Speranza (1971). Ancients Legends, Mystic Charms, And Superstitions of Ireland. Ireland: O’Gorman. First published in 1887.

- Hatherley, Owen (2016). The Ministry of Nostalgia. London: Verso Books.

- Weber, Max (1985). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. First published in 1930.

- Soelle, Dorothee (2006) Dorothee Soelle, Essential Writings. New York: Orbis Books.

- Asad, Talal (2003). Formations of the Secular; Christianity, Islam, modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Stengers Isabelle (2012). Reclaiming Animism. e-flux Journal #36. Available here.

- Starhawk (1993). Dreaming The Dark: Magic, Sex and Politics. New York: Beacon Press.

- Stengers, Isabelle (2011). Capitalist Sorcery, Breaking The Spell. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Steedman, Carolyn (2001). Dust. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

by Ella Sweeney and Reid Calvert