Microcosms of Garment-Perception

Mati Hays and Johanna Owen consider the cosmic quality of the colour black

The first-ever image of a black hole revealed to the world in April 2019. Image from Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

The following is part of a body of research which examines the intuitive expressions of black hole physics as a pattern within society. What you are to read is a small part of an ongoing and forever-growing archival collection of words, images and ideas which constitute this theory. We will call this theory garment-perception,1 a psychic process of reverse engineering garments out to the cosmos in order to locate lost values (unknown speculations) of human consciousness. Through doing this we see that the garment is, in fact, conscious matter.

This work connects the construction of specific cultural moments to the structure of black holes from their genesis as developing stars. The role of gravity will be scrutinised through the lens of colour theory, with a focus upon the colour black. A new theory for fashion relativity will be proposed by contrasting the expansive force of dark energy with the implosive force of gravity.

There is a particular paradigm of garment perception which is enhanced by the sociomaterial mimesis of tension at the site of black holes. We can identify this paradigm through garment perception in an industrial framework, populated by garments, architecture and corporate franchise.

For now, as we do not have forever, we will evoke only a few moments which concern the colour black to examine: a dead garment in the living archive of Cristóbal Balenciaga; a pigment made from carbon nanotubes; the Ancient Egyptian conception of craft; The Little Black Dress, Fordism and Hollywood in the 1920s; and the franchise tactics of Hot Topic as witnessed through a t-shirt worn at Berghain.

A dead garment in the living archive of Cristóbal Balenciaga

Collections Specialist, Igor Uria, lays out the Dress Which Mourns Itself for examination. Image by Mati Hays, June 2019

In July 2019 Mati Hays visited the Cristóbal Balenciaga Museum in Getaria, Spain and was granted a private tour of the archive to learn about the methodologies used to preserve and present the collections. During their meeting with the collections specialist, Igor Uria Zubizarreta, Hays asked to see what the specialist thought was the biggest failure of the archive. He pulled a garment bag from the vault and carried it up to the examination room. As he opened the bag on the table he said: “We have no idea what has happened to this dress. It is not supposed to be the colour black.”

The Dress Which Mourns Itself: I think about this moment every day since it happened.

In the cellar of the main collection I asked “What is the biggest failure of the archive?” Without hesitation, he twisted the stile to unlock a large vault and removed a sealed hanging garment bag, returning it to the preservation room where we could properly examine the failure which lies inside. “It is a 1950s cocktail dress donated by a woman in New York” he says, “we do not know what has happened to this dress. It has turned the color black?!” He lifted the hemline wearing black gloves to show that the dress had originally been the color gold. There are also puddles of green acidic-looking splotches spreading disease over the dress.

– Mati Hays: Notation on The Dress Which Mourns Itself. February 9, 2020.

Why is it that within the world of the museum narrative, The Dress Which Mourns Itself is considered a failure?

What is striking is the quality of consciousness within this object in expressing its own demise. It is both cryptic and defiant. Consciousness, or meaning, has not been projected onto it by a process of preservation. Rather it is as if the dress has taken its fate into its own hands, defying the historiological process. The reasons behind its ruinous state cannot be explained within the examination room so cannot serve as an explanation of its own industrial decomposition. It is pure, opaque poetry.

Michel Foucault traces a paradigm shift in the form of power which he dates to the eighteenth century. The rise of biopower in the eighteenth century led to a shift that is characterised as:

[…] a power bent on generating forces, making them grow, and ordering them, rather than one dedicated to impeding them, making them submit, or destroying them. There has been a parallel shift in the right of death, or at least a tendency to align itself with the exigencies of a life-administering power and to define itself accordingly […] a power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations.2

To take one’s life into one’s own hands, even if it means to perish, is a scandalous act in the realm of biopower described by Foucault. To die a death unplanned for you by the hegemony of civilisation is to defy the preservationist force of the museum which allocates death to matter according to a formal system of inherited value.

The museum is a chamber in which we wish to simulate a permanent depiction of life. This simulation aligns with the paradigm of biopower that Foucault identifies. Rather than being activated by the destruction of life, the museum chamber is activated by controlling the lifespan of artifacts and contextualising the narrative of life within a controlled construction. The simulation of permanence is only a facsimile achieved by technological advancements in preservation. For these reasons, the museum is a space that is borne from an attempted void.

No, a black hole is kind of the opposite of a void. As you said, a void is a region of nothingness. A black hole is a super-dense accumulation of matter, usually a collapsed star. It got its name because its gravitational pull is so strong, not even light can escape. So anything that gets too close to it gets pulled toward it. ‘Black hole’ is a pretty good description of what it looks like.

But keep in mind that ‘void’ is a colloquial term referring to the vastness of space, while ‘black hole’ is a scientific term referring to a specific phenomenon.

– Reddit user raendrop. 2017.

As raendrop points out, colloquial conceptions of space often refer to a ‘void’ of nothingness, where ‘nothing’ is happening. However, there are no known pockets of the universe that remain devoid of energetic interactions. Even in the vacuum of space the dark energy constituting 68% of our universe is understood to be an energetic field which spawns the acceleration of universal expansion. Dark energy is the last remnant of our reality which is undefined but understood to exist. It is released when particles and their direct opposite – antiparticles – collide.

Dark energy can be seen as the essence of life around which the conception of garments are first draped. The physical construction of any vital garment3 is a force reaction to facing the inner and outer world simultaneously. Through this vitality one’s own perception changes by way of the garment being filled.

Particles of dust and gas assemble into galactic swathes of fabric. Integral to forms of surviving reality, in garmentry the needle is the most powerful strength of gravity as it wedges between particles of fiber to the point of puncturing through them. Light threads this needle. Because gravity pushes and pulls particles to such a position, light curves around them and absorbs into the punctures that gravity has opened. These punctures are black holes: areas which shirr our reality – nearly all large galaxies contain a supermassive black hole at their core.

The universe is a garment on which gravity works as a cosmological needle. The gravity-needle is an invisible force of labour that makes the world which we perceive viable. The force of gravity assembles dust and gas clouds that eventually condense, collapse and create stars. Light from these stars – starlight – is the source of electromagnetic radiation which interacts with optic sensing. Human perception of colour is derived from this physiological interaction. If stars are large enough, the pressure of gravitational assemblage leads to the implosion of its stellar core from which dust and gas-clouds are spewed out in the form of nebulae. The location of implosion excretes a nebula and becomes the puncture point of the black hole. Star-death is the genesis of our solar system – the vantage point from which we perceive the garment of the universe as reality. The universe is then a garment-reality, for in order to have garment perception, we must have a reality for perception to sense.

Microcosms of garment perception begin at their expulsion from the black hole.

The conscious development of punctures in garment construction enhanced a physical tension of dominant force. The oldest known bone needle crafted by hominids for the purpose of creating garments with threaded punctures dates back 50,000 years ago.4 Bone needles were used by Homo sapiens as well as by other archaic human species – the Denisovans and the Neanderthals. The use of punctures in garmentry is then quite fundamental to our survival history, as the tension that held garments and shoes together protected us, kept us warm and allowed us to traverse the terrain. The integrity of the garment-reality is maintained by this particular tension. The concentration of tension at the location of the black hole prompts us to contemplate apocalypse – the destruction of the garment, the end of the world.

For humans, death is where the perception of the individual ends. But the planet goes on after we are dead, it will exist with or without humans around to witness its life. The difference between apocalypse (the end of the world) and extinction (the end of life) is a form of tension. Genetic origin, as well as the biblical idea of ‘genesis’, is the origin of this particular tension. Genesis divides human reality from the reality of planet Earth.

We observe traces of genesis, of knowing that we cannot comprehend the fullness of reality, when we witness the colour black. Black is what humans see when all lengths of visible electromagnetic waves are absorbed away from the eye. In this sense, the colour black is both the absence of visible light away from the eye as well as the total presence of light where it is absorbed, making it highly energetic. When we encounter the colour black we surrender to the absurdly limited nature of human perception.

Our perception of reality involves an acceptance that our existence in this universe is temporary. This understanding I will hereon refer to as ‘mortal sensuality’. To elaborate, mortal sensuality is the physiological reaction to this tension – the push and pull of mortality – which holds our life together. Because of the way in which black holes absorb everything, they threaten us with the ultimate surrender to our mortal predestination: the return to the star-death from which our sun and planet were spewed.

By emulating the black hole, by absorbing itself and turning black, The Dress Which Mourns Itself stimulates the tension of mortal sensuality that the void attempts to placate. This is why an object like this dress, which visibly demonstrates its own decay, is a failure of the museum. It indiscreetly reveals that voids are vulnerable to the absorption of non-artificial life. That a dress would express this collapse into itself by self-saturating to the point of blackness is a poignant reference to the black hole.

A pigment made from carbon nanotubes

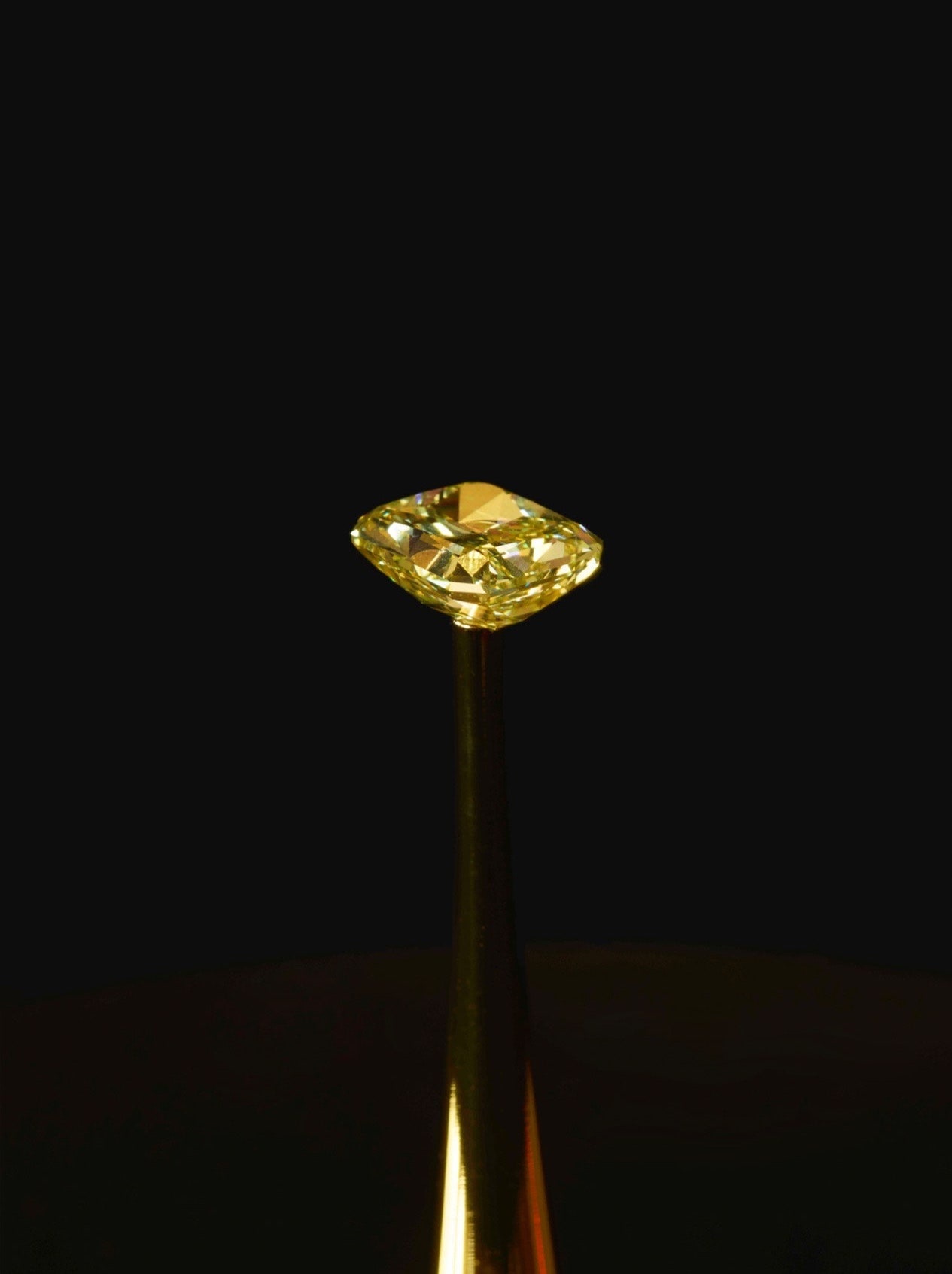

Redemption of Vanity by Diemut Strebe

The way in which black pigment on Earth reminds us of our mortal predestination is through a representation of the deep black of space. Many of the pigments that we perceive as black are in fact a facsimile of total energy absorption, accomplished by a layering of materials upon one another.

Humans construct static voids, like black pigment, in order to fill them with a preserved virtual reality. These voids act as chambers through which the physical forces of reality are channeled. The lifecycle of these voids have been extended by the use of preservative and durable materials like pigment fixatives and plastics.

Although these materials will outlive a human life, because they eventually decay they cannot make immortal voids, only temporary ones. In this sense, voids necessarily lose any potential of static permanence by coming into contact with the ephemeral, motive materials of nature which characterise mortal sensuality.

The physical process of producing artificial black pigment throughout history is particularly concerned with the mortal, ephemeral quality of materials. Black was the first pigment to be used in prehistory, often in the form of carbon soot – the cremated remains of organic matter.5 In this sense, artificial pigmentation begins with the sacrificial expiration of life.

The Ancient Greeks had no material that could serve as a fixative for artificial dyes. Colour was perceived as fluid and ephemeral because they could observe the fading and changing of colour over time. As civilization developed, dying textiles black involved a time-intensive procedure of soaking fabric first in a blue woad or indigo bath and then over-dyeing it with red madder. Metallic mordants were then used to preserve colour, causing the textile to degrade. This lent black textiles a high production and replacement value.

The deepest gradation of black saturation within our galaxy is the absolute absorption of light at the site of a black hole. This is cosmic black. As artificial black pigment imitates this absolute absorption of light it is less saturated than the truest black of a black hole. Entities that turn black without being artificially engineered to do so mediate the human relationship between cosmic black and artificial black.

Vertically Aligned Carbon NanoTube Array Black, or Vantablack, is made up of a dense coating of carbon nanotubes which absorb 99.96% of light. In September 2019, MIT engineers developed a blacker black and produced a pigment which absorbs 99.995% of light. The engineers are motivated to manufacture this ultimate black in order to coat spacecraft whose function is to sense light from distant objects. The light of our solar system bounces off these spacecraft and can create noise which muffles what the system picks up. By coating spacecraft in the ultimate black, a reduction in noise would allow us to see into deep space from the perspective of a black hole.

The quest to find the blackest black has attained aspirational vanity by its use in the art world. Artist Anish Kapoor is well-known for obtaining exclusive rights to the use of Vantablack from Surrey NanoSystems in 2014. Many of the works that Kapoor has made with the pigment are simulations of black holes – circular holes made from Vantablack paint installed on gallery floors and walls. His monopoly over the technology has been met with harsh criticism and, in one case, a form of revenge. The artist Stuart Semple has manufactured both a ‘pinkest pink’ and a ‘Black 3.0’, both of which are “available to anyone who isn’t Kapoor”.5 After the team at MIT improved slightly upon the original Vantablack they made the updated pigment available to artist Diemut Strebe. Strebe’s Redemption of Vanity, a 16.78 carat yellow diamond coated in carbon nanotubes, which makes the diamond appear to disappear, debuted at the New York Stock Exchange in September 2019.

Carbon nanotubes also exhibit remarkable conductivity, making them potential replacements to silicon as a superior material for transistors – the building blocks of computer microprocessors. Carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNFETs) are more energy efficient than silicon chips. CNFETs can be manufactured at room temperature, allowing for three-dimensional chips capable of combining logic and memory functions. Here acceleration has become simultaneity, and simultaneity is static.

A carbon-based structure for computer microprocessors and nanotechnological pigment is compelling in its connection to the biological, to the organic and to the black carbon soot of Paleolithic pigments.6 The conductive potential of carbon nanotube microprocessors could bring us one step closer to introducing the cognitive bioelectricity of a brain or the respiration of breath to a machine. Imagine the transistors crackling like burning leaves as electricity shoots through them.

While black holes may be colloquially mislabeled as ‘voids’, their power is not in acting as spaces of emptiness but becoming spaces of total absorption. Humans conceive voids and construct artificial chambers which are filled by the absorption of physical mass and energy. In this sense, the voids that humans construct through artificial pigments are an indirect imitation of the absorptive totality of black holes.

The Ancient Egyptian conception of craft

Craft in Ancient Egypt was a formal attempt to construct a voiduous space in which life could be rebuilt according to the will of humans. Eventually, this realm would be inhabited by the citizens of Ancient Egypt according to the fashion in which they constructed their burial site. To preserve oneself in a depiction of the life that you wished to inhabit in the other realm was the ultimate privilege. Otherwise, you would simply be procured as furniture for the tomb of someone with a higher status to serve them in the next life.

The Ancient Egyptian language has no word for ‘art’, but it had words for ‘statue’ and ‘tomb’. It also has a word for the craftsmen who employed technology in the production of artifacts (hemutyu) and for those understood craft trades in relation to their associated tools and products (hemut). Artifacts were crafted to mediate ritual and were understood as functional components of a religious infrastructure. The Ancient Egyptians “had a sense of the aesthetic but within a function.” Artifacts were “functional within the religion.”7 Statues were designed to perform functions: for example, arms were extended to hold objects.

The depiction of a subject through a crafted artifact was understood to render that depiction into permanence. Therefore, the depictions of the hemut served to render an idealised vision of the world which would be manifested in the afterlife. Figures were positioned in the midst of tasks that they were to serve in eternity. Much like projected futures in 3D animation, Ancient Egyptian artifacts were understood to form a virtual reality that would eventually merge with the landscape of the real. The conscious focus upon the tools of craft as the engineering mechanisms of reality is continuous with a conscious understanding of the force of gravity as the sculptural force of the visible universe. On a human scale, we channel this gravitational force to craft virtual renditions and future realities.

In this light, it is interesting to note that the nature of the Internet works as though it is a permanent space, not a fragile, temporal one. We have developed no widespread technique for preserving the Internet in other formats – if the electric grid were to be wiped out, all this information would disappear. Perhaps, on a subconscious level, we view the Internet as a preservational space for a secular afterlife similarly to how Ancient Egyptians viewed their tombs.

The Internet itself functions similarly to the colour black: it absorbs, stimulating a sense of our mortal nature. The original net interface displayed green text against a black background but, as it became more widely used, the display was changed to black-on-white for the sake of legibility.

The Little Black Dress, Fordism and Hollywood in the 1920s

Chanel’s little black dress on display during the Chanel: The Legend exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, 2014

When it was first created, Coco Chanel’s Little Black Dress was viewed as a bold statement both because it was black and because it was simple. Introduced in 1926, Chanel’s intention was that the garment should be “available to the widest possible market” in a move that “revolutionized fashion”.8

Vogue labeled a drawing of one of her Little Black Dresses “The Chanel ‘Ford’—the frock that all the world will wear”9 in a direct reference to Henry Ford’s 1908 invention of the Model T which was, famously, only available in black. The Model T marked the advent of a marketable, mass-produced form of transportation for the individual. Ford’s development of the assembly line became the infrastructure of Fordism: the dominant system of industrial production and consumption in the 20th century.

The Little Black Dress was fashion’s parallel to the Model T as it marked the acceleration of mass-production within the garment industry. The Dress became a staple of ‘ready-to-wear’, the fashion industry’s term for ready-made garments. In its reproducibility it fetishised the utilitarian nature of workwear, a kind of clothing which would have been worn by those who could not afford such a dress: the working class of the early 20th century.

It was also similar in shape to simple black uniforms worn by domestic servants before the 1920s.10 As stated by French artist Urbain Checcaroni, the French term for ready-to-wear, prêt-à-porter, is literally translated as “ready to carry” or “ready to bear”. Chanel offered a populist garment by elevating the servant’s smock to a desired object. It conflated domestic industrialism with mercantile aristocracy in an appeal to the growing development of a ‘progressive’, prominent middle class. It was the birth of a fashion uniform.

As stated by the retail technology firm Edited, the Little Black Dress has become the “staple black dress forming the core of most female shopper’s wardrobes”.11 In 2014, Edited published a market analysis of more than 183,000 dresses retailing online in the US which revealed that approximately 38.5% were a shade of black, making it by far the most common colour available. The second-most popular shade, white, only represented about 10.7% of dresses.

The appearance of the Little Black Dress in early Hollywood was a major contribution to the industry’s popularity. The Dress was first debuted by Clara Bow in the 1927 hit film IT, directed by Clarence Badger and Josef von Sternberg. In the early days of film, when everything was shot in black and white, film stars knew to utilise black costume in order to accentuate the projected image. Black garments and makeup enhanced the gestural impressions of face and body. The contrast of eyeliner or black clothing also illuminated light-skinned actors, making them glow.

The spherical surface of a black hole is known as the event horizon, beyond which no light or radiation can escape. At this horizon, extreme gravity pulls pairs of particles and antiparticles apart. Particle-antiparticle pairs swirl within magnetic and electric fields. Electrons and their antimatter counterparts, positrons, move in opposite directions around the disc of the black hole’s equator. Their currents cause energy to stream out of plasma jets at the polar regions of the black hole. The negative particle is absorbed by the black hole, reducing the black hole’s energy and mass. The other particle is emitted out to space as electromagnetic radiation. The black hole, then, is not only a site of absorption but also a site of energy projection.

So the film camera is also a black hole. The surface of a film projection involves the relationship between absorption and projection, the negative and the positive. Like all matter at the horizon of a black hole, the mortal statues of the studio stage are absorbed by the lens. Upon projection, their gravitational imprints absorb the weight of shade in the theater and emit visible light outward into space, across the field of the audience.

The concept of faciality in the chapters of Cinema 1: The movement-image from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s book A Thousand Plateaus touches closely on the absorptive and projective space of the screen in reference to the black hole. As summarised by Tom Conley:

Subjectivation and significance are correlated, respectively, with the ‘black hole’ or unknown area of the face in which the subject invests his or her affective energies (that can range from fear to passion) and with the ‘white wall’, a surface on which signs are projected and from which they rebound or are reflected. Faciality is thus constituted by a system of surfaces and holes.12

Every developing star, whether in outer space or in the movies, is a black hole waiting to happen. Cultural energy is transferred from one black hole to another: the stage → the movie theater → the television → the monitor.

The franchise tactics of Hot Topic as witnessed through a t-shirt worn at Berghain

Part of the interior of Berghain, called ‘Halles’. Ventilation hoods and large structural columns evoke the reality of the original architecture of the power plant, as it is currently being optimised for the design of an industrial techno club

Where Hot Topic started their company— inside a Southern California garage, 1989

Mati Hays’s 3D rendered animated prototype of a planned artwork. Animator: Ethan Skaates

The dance club Berghain is a curated iteration of the supermassive black hole. It is a self-aware void. Rather than resisting the momentum of gravity, Berghain is a chamber that channels the absorptive activation of the black hole in order to power itself. Like an hourglass or a powerline, clubgoers filter through its channel in order to animate the infrastructure, like granules of sand or volts of electricity. Berghain is the architectural remnants of a power plant. Like artificial black pigment, the void of Berghain is engineered to absorb at maximum saturation.

As stated by the infamous doorman of Berghain, Sven Marquardt, the club does not have a dress-code but due to the bouncer’s personal preference to often wear black, there is a perception that those in the queue should follow suit to gain entry.

Silhouettes in the queue who do gain entry converge in the absence of light inside. Here cameras cannot see as there is a strict no-photos policy. These silhouettes are now blending, forming into one. The void is filled by a vibrating unity.

Within this swirling, there is white vinyl lettering in Impact typeface on a short-sleeved tee:

I’ll Stop Wearing Black When They Invent A Darker Color.

Here is a tacit declaration of one’s lack of agency over the machine of fashion. An acknowledgment of one’s inability to be both the inventor and the wearer – a failure of simultaneity, a refusal. The stark contrast between the technicians (those who engineer the infrastructure) and the techthletes (those who use the technology athletically).

The t-shirt is sold by Hot Topic. It is arbitrarily ripped from the quotebook of Wednesday Addams of The Addams Family. The genius of the Hot Topic economic digestive system lies in its semi-arbitrary recycling of culture that capitalises on an off-center niche. It locates the algorithm at the asymmetrical point of ‘alt’ culture and sucks everything up to orbit the vacuum hole of licensing agreements. Hot Topic offers “100% Officially Licensed Merch. If you find it at HOT TOPIC- It’s LEGIT… All of our merch is vetted and sanctioned by its intellectual property owners to ensure its authenticity…”

Founded in a southern Californian garage in 1989, the business model hacked the DIY architecture of band merch by mining the licensing industry for major returns. Hot Topic does not so much offer a product as much as it offers the service of buying and selling intellectual property on a mass scale. To anyone who views this t-shirt out in the world, the reference to its origin is completely lost on those who don’t have its reference mnemonically stored within their brains. Instead, the shirt becomes a reference to its own failure to be original.

Unlike The Dress Which Mourns Itself the t-shirt does not embody a consciousness of its own. Rather, like all slogan t-shirts, it is an object of ventriloquism. A voice both dense and hollow is thrown on to the object from an unseen licensing agreement. The t-shirt becomes an ironic expression of the industrial process from which it has emerged.

The garage in which it was founded is a replicant from the genetic network of garage culture13 – a network composed of many garages across the United States of America in which the contemporary, corporate project of virtual reality has origins. Garages are not only where the most industrious construction tools of the household are often stored, many of the most powerful projects devoted to the craft of culture absorption were born within this network: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell, Verizon, Amazon, Disney, Hewlett-Packard and Virgin were all started in garages.14

This garage network is the primary evolution of the contemporary void-space. The original Hot Topic garage was an offshoot of this network which replicated itself within the chamber of the void-cluster (also known as the shopping mall).

The t-shirt is a reference to its own artificiality within a virtual space constructed by garage culture. The artificial imitation of a black hole is made obvious. The shirt proclaims: I am not the original. The artificial dye on the t-shirt hints at its failure to be the cosmic black that is only seen at the core of the galaxy.

A new theory of fashion relativity

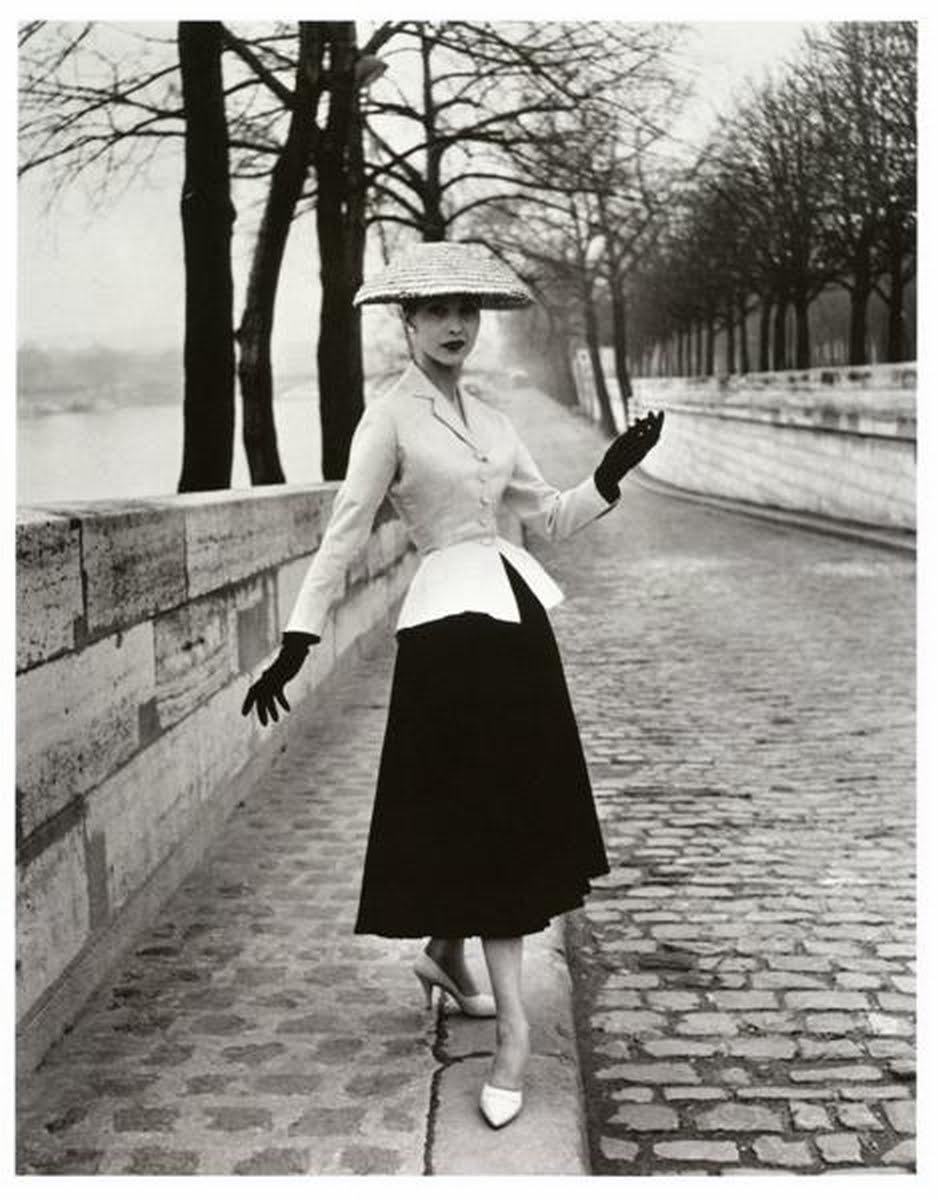

Infamous Christian Dior bar suit, photographed in Paris, 1947. Image from Getty Images

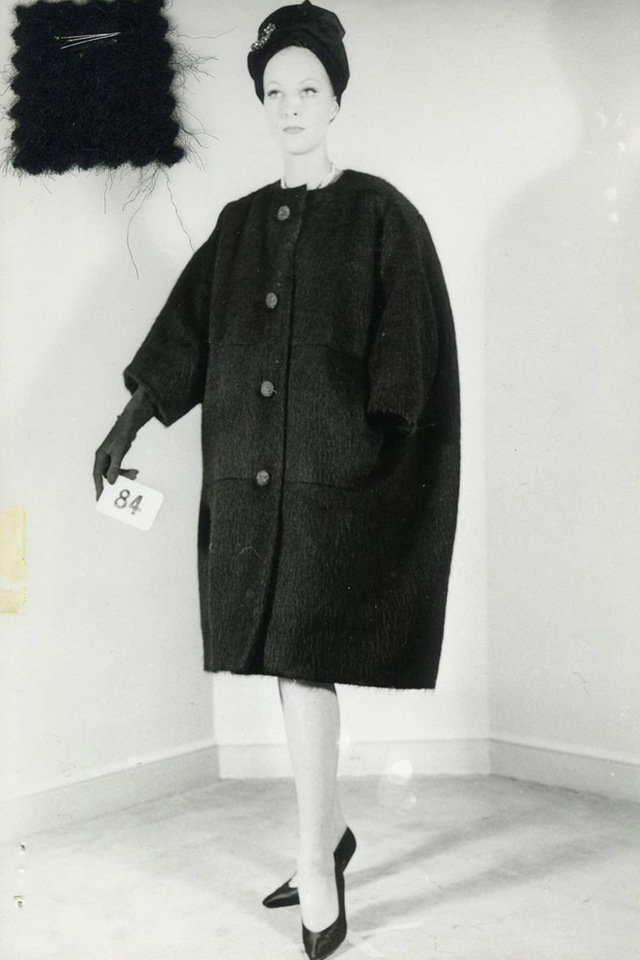

Cristobal Balenciaga’s “Barrel Line” silhouette defines one of his “cocoon coats”. 1960. Image from Balenciaga Archives Paris

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity predicted the existence of black holes in 1916, at the height of World War I. The Theory of Relativity encompasses two interrelated ideas about the nature of gravity in the universe. The theory of special relativity found that “space and time were interwoven into a single continuum known as space-time.”15 The general theory of relativity found that massive objects created distortions in this fabric of space-time, causing it to warp. It became clear that massive stars would collapse into themselves after losing the ability to support their own weight, causing a distortion in the space-time continuum known as a black hole.

Einstein’s theory depicted an implosive universe, one in which gravity caused the assemblage of matter in the universe to contract into itself. According to Einstein’s work, gravity should have been causing the universe to shrink. Einstein added a repulsive force to his equations called the cosmological constant to accommodate the axiom of a steady-state universe – the fundamental idea that the amount of matter in the universe is eternal and constant, even as it may move and change forms. Without the cosmological constant, Einstein’s theory of general relativity would mean that gravity was causing the universe to self-destructively collapse.

The 20th century, the era of the general theory of relativity, was characterised by this neuroses of self-implosion and a repulsive force against it. Voids became about the nuclear: the implosive pressure of matter and the compression of industry into a standardised, measured flow of units through a line, whether it was that of Ford’s assembly or the domestication of the electric grid.

This pressurised flow of units through a chamber became the infrastructure through which we lived out our experience of time. Like an hourglass, the movement of granules through a constricted chamber animated our conception of reality.

Christian Dior’s New Look was a perfect interpretation of this hourglass mentality of time. Introduced in 1947, Dior’s Bar Suit featured rounded shoulders, a cinched waist and a full skirt. It was a brutalist re-structuralisation of the corseted Victorian silhouette that defined the ‘hourglass shape’ of mid-century modern femininity.

Fashion was characterised by a reactive exchange of silhouettes in the year 1947, which was also the year that a direct opposite of the cinched hourglass form was introduced by Cristóbal Balenciaga. Balenciaga’s designs were anti-hourglass and would go on to characterise the dominant cultural figures of the 1960s. In February 1947, Balenciaga introduced the “barrel” line, “which departed from the dominating aesthetics of confined figures and emphasized fluidity in its design”.16 Founded in 1937, the Balenciaga fashion house became distinct for its expansive silhouettes in such forms as the babydoll dress, the spherical balloon jacket, the cocoon coat and the sack dress. Balenciaga shapes broadened the shoulders and removed the waist, blowing the silhouette out into a globe.

By the 1990s, exploration of dark energy had confirmed that the aspect of Einstein’s theory which points towards a static universe, a cosmological constant repulsing against the impulse of contraction, was wrong. It was discovered that the expansion of the universe is actually rapidly accelerating due to the mutual annihilation of particles and antiparticles in deep space, producing dark energy.17 The vacuum of space, previously conceived as a voiduous space of stillness, is in fact the edge of our reality which continues to rapidly expand.

The discovery of an accelerative, expansive force has given rise to a new form of neuroses in the 21st century. Rather than being characterised by the constrictive repulsion of the gravity-obsessed 20th century, the 21st century is defined by an anxiety of acceleration and endless sprawl – the seemingly uncontrollable spread of information on the Internet, ketamine-fueled dissociations and schizoanalysis and accelerationism’s expansion over the cutting-edge of philosophy. Underlying all of it is the sensation of being ripped apart by the universe. The expansion of space tells us that we are not still. Rather, we are pulled up in the momentum of spread.

It is time for an apithological approach to the theory of relativity and to the expansive awareness of the 21st century. We must realise that it is the tension between two dark forms – the black hole and the dark energy in the vacuum of space – that holds us in place within the whirling momentum of the universe. Our momentum has form: it is shaped by the push and pull between that gravitational implosion around which our galaxy moves and the billowing expansion of deep space tugging at our outermost edges.

The psychic process of space-time travel guided by a sensual awareness of garment making is an antidote for the neuroses of fashion as an infrastructure. We must be put back into our place by experiencing the garment within its moment. The consciousness of a garment is characterised by both the filling and extending of a void that exists only in our minds. The garment, like the universe, is never static but shaped by an assemblage of matter through time. It lives in many forms as its energy is recycled and its matter reshaped.

We are never looking out at the void and the void cannot look inward without imploding. Rather, the void is reversible. It is that space between – it is us, our physical and conscious existence. Perhaps we do not imagine the universe, rather, we are imagined by the universe – by the totality of matter filling and expanding the tension of our form through the rotational movement of costumed dance.

In learning to resist, the body goes beyond its individual intention, and reveals an emergent,

unexpected meaning occurring within a space of tension […] The dancer’s experience of falling exposes a playful relationship with gravity. Through this movement where the body has no gravitational support and accelerates towards the ground, the body learns to use the threshold of the ground, and experiences risk as the weight of its own mass. Immersed in the gap of support, the dancer experiences momentum – a sense of travelling in the flux of time. And within the sensation of vertigo he feels the body vibrating between the paradox of excitement and fear. Whereas in a static understanding of the world the notion of duality is perceived as a disadvantageous conflict of formal oppositions, in a motional understanding of the world, this conflict is the drive of becoming alive.18

– Cecília de Lima: Trans-meaning— Dance As An Embodied Technology of Perception. October 2013.

- “It is important to look deeper into artistic practices that develop an embodied access to systems of perception. These practices touch the very core of our means of ‘re-cognition’ and, as such, they need to be considered as specialized experiential technologies of our cognitive processes.” – Lima, Cecília. (2013). Trans-meaning – Dance as an embodied technology of perception. Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices.

- Foucault, Michel (1978). ‘Right of Death and Power Over Life’ from History of Sexuality. Translated by Hurley, Robert. New York: Random House and Editions Gallimard.

- “How would political responses to public problems change were we to take seriously the vitality of (nonhuman) bodies? By ‘vitality’ I mean the capacity of things, edibles, commodities, storms, metals-not only to impede or block the will and designs of humans but also to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own. My aspiration is to articulate a vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans to see how analyses of political events might change if we gave the force of things more due.” – Bennett, Jane (2010). Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Siberian Times (2016). World’s oldest needle found in Siberian cave that stitches together human history. Siberian Times. Available here.

- Cascone, S. (2019). Anish Kapoor Owns the Rights to the Blackest Color Ever Made. Now Another Artist Is Making His Own-and It’s Even Blacker. ArtNet. Available here.

- Carbon is frequently referred to as ‘the building block of life’ at the most fundamental level of education in biology. The author was unable to determine who first characterised carbon with these words.

- Royal Society of Chemistry (2015). Royal Society of Chemistry. Principles of Egyptian art. Available here.

- Eschner, K. (2017). Why Coco Chanel Created the Little Black Dress. Smithsonian Magazine. Available here.

- Borrelli-Persson, L. (2020). Everything You Need to Know About the Little Black Dress. Vogue. Available here.

- Puhak, S. (2017). The Underclass Origins of the Little Black Dress. The Atlantic. Available here.

- Smith, K. (2014). Could you guess the best-selling colors in dresses for SS14? Edited. Available here.

- Conley, T. (2005). Faciality, in Parr, A. (ed) The Deleuze dictionary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- The idea of architectural DNA as part of a reproductive network is inspired by the unpublished essay ‘Buildings are sentient and evil’ by 111111111.00.

- DeFoore, S. (2016). 12 Big Companies that Started in Garages. San Antonio Door. Available here.

- Redd, N. (2017). Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. Space.com. Available here.

- Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa. (2019). Cristóbal Balenciaga, Fashion and Heritage [Brochure]. Getaria: Cristóbal Balenciaga Museoa.

- NASA. Dark Energy, Dark Matter. NASA. Available here.

- Lima, Cecília. (2013). Trans-meaning – Dance as an embodied technology of perception. Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices.