Parasitical Sublimity

Tenant of Culture shares some thoughts on mud-coats, patina and authenticity

1

This video is a research project conducted in the north of Friesland, a part of the Netherlands that my family is from. In autumn the soil gets incredibly muddy. This mud is as soft as silk and has the consistency of thick yoghurt. I’ve never encountered this type of soft mud anywhere else. At this point, plodding through the fields in September, when the mud is at its wettest, I started to think of it as an archive without a selection process. During these walks I would find all sorts of things stored in it; animal bones, wrappers, sea shells, a pair of scissors, gloves, a fork, a single wellington. All of these were covered in a thin layer of mud, giving them a uniformity in colour and texture. This system of the inclusion of objects, whether organic or manufactured, valuable or worthless, being encapsulated and stored inside the mud seemed to me to be very hospitable. The process of objects being included and excluded from other kinds of archives is based on a selection process of value assessment, but here in this muddy field the objects were sucked in, stored and protected.

2

Mud-coated jumper. Friesland, 2017

The history of Friesland is muddy. Being underneath sea level its inhabitants have had to grapple with living on drenched soil since the beginning of time. The ground was too soggy for carriages or horses and by foot it was difficult to get around. The side of my family that is from this region attributes this to an absence of religion in the family: missionaries weren’t able to make it far into this muddy place, allowing for paganism to flourish whilst the rest of the country converted to Christianity. When the Roman army came to conquer the Netherlands, one of its commandants Plinius the Old notes that he couldn’t distinguish whether they were on land or at sea. He couldn’t tell whether the houses the Frisians inhabited were shipwrecks or farms. He believed it was pointless to attempt to take over this region as its people were more fish than human.1

3

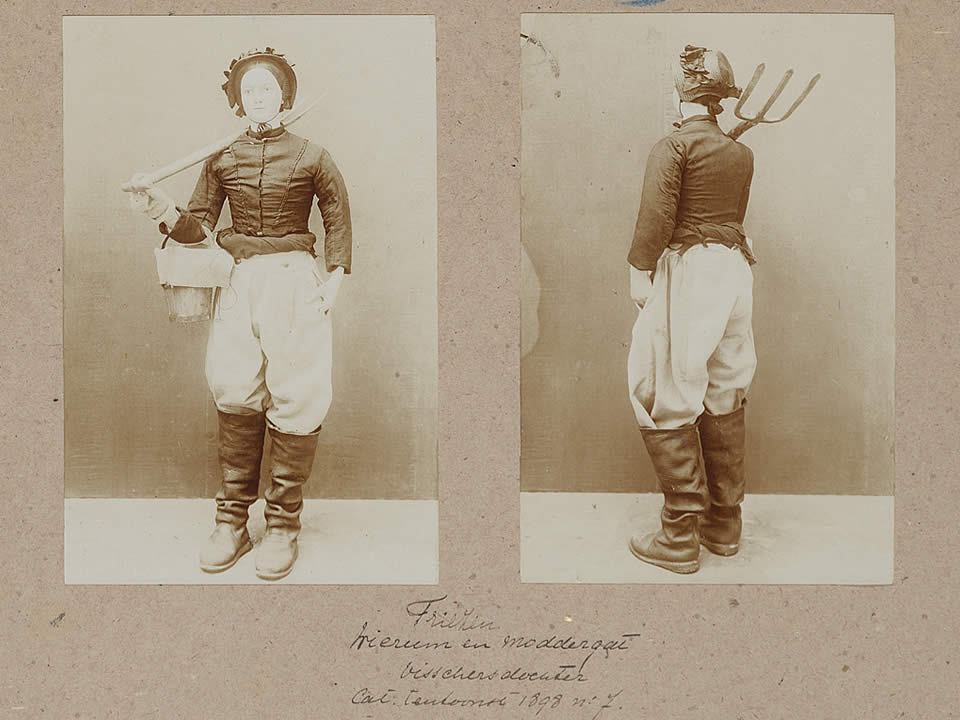

A mannequin wearing the working garments of a ‘dolster’ from Wierum or Moddergat, front and back. The images were taken during an exhibition on regional dress in 1898. Photographer: H. Bickhoff. Collection Nederlands Openluchtmuseum

In the very North of Friesland, on the coast of the North Sea, there is a town called Moddergat. In English, this translates as Mudhole. In the 19th century, the main source of income for this town was fishing, a task carried out by men. The women of the village would remain on land to roam the mudflats for worms that were used as bait. They wore thigh high leather boots, into which they tucked a generously cut pair of under trousers. Their skirts were rolled up and attached to a bodice and jacket. My father once lost a pair of wellies in these same mudflats as he got stuck in the succulent earth. The only way to escape was to leave his boots behind. He emerged from the mudflats wearing only slushy socks, stinking of sulfate.

4

PRPS Barracuda Straight Leg jeans

The idea of mud as a decorative layer became a topic of discussion in 2017 when clothing firm Nordstrom released the PRPS Barracuda Straight Leg jeans. These were newly manufactured and coated in mud, all for the modest price of $425. The company branded the apparel as a pair of jeans “that shows you’re not afraid to get down and dirty”, directly appropriating the work class ethics of manual labour, laying bare the ambiguous relationship between luxury fashion, industrial production and class hierarchies. This particular pair of jeans became a turning point in the public perception of the pre-existing market of artificially stained and distressed clothing. In his essay Authenticity is a Con Professor Andrew Potter discusses the question why exactly this pair sparked such controversy when the:

PRSP jeans have been around for years, available in a wide range of pre stressed, aged, worn, washed and generally beat up styles, all retailing for well north of US$250. PRSP has long been held up as the acme of denim clad working class authenticity. Made in Japan on 1960s-era looms, using organically grown cotton sourced from Africa, the label owner once said he was inspired by the denim work by actual workers before jeans became middle class leisure wear.2

5

In his well known and often referenced Theory of the Leisure Class, Thorstein Veblen makes a similar observation regarding the stylistic appropriation of manual labour by the upper classes or ‘leisure class’. He observes that in order to successfully convey status one has to simulate the veneer of labour, denoting usefulness. In the 19th century these activities were were hunting or learning obscure languages. For women this included dressing as milkmaids and spending time in follies of mock-dairy farms. But these activities were always the sterilised version of the actual labour appropriated, to demark a clear distinction between the clean and the dirty.

[…] there are few of the better class who are not possessed of an instinctive repugnance for the vulgar forms of labour. We have a realising sense of ceremonial uncleanness attaching in a special degree to the occupations which are associated in our habits of thought with menial service. It is felt by all persons of refined taste that a spiritual contamination is inseparable from certain offices that are conventionally required of servants. Vulgar surroundings, mean (that is to say, inexpensive) habitations, and vulgarly productive occupations are unhesitatingly condemned and avoided. They are incompatible with life on a satisfactory spiritual plane – with ‘high thinking’. From the days of the Greek philosophers to the present, a degree of leisure and of exemption from contact with such industrial processes as serve the immediate everyday purpose of human life has ever been recognised by thoughtful men as the prerequisite to a worthy or beautiful, or even blameless, human life. In itself and in its consequences the life of leisure is beautiful and ennobling in all civilised men’s eyes.3

6

Artificial ageing has been common practice since the ancient Romans began to produce “weathered” copies of Greek art. In the Renaissance patina began to be used on new sculpture. Then, in the 17th century, paintings were artificially aged using varnish and other techniques and put in decrepit frames to further the effect, often to the advantage of forgers. By the 18th century a common view among art connoisseurs was that time made a picture more beautiful. In the 19th century the effect of age was particularly valued in works of art and architecture – the British critic John Ruskin was the most famous exponent of this aesthetic. “Fortunately for mankind” he wrote:

as some counterbalance to that wretched love of novelty…which especially characterises all vulgar minds, there is set in the deeper places of the heart such affection for the signs of age that the eye is delighted even by injuries which are the work of time. The greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, nor in its gold. Its glory is in its Age…it is in the golden stain of time that we are to look for the real light, and color, and preciousness of architecture.4

He had little to say, however, about the signs of age in paintings, except to commend “the golden tone that time has left”. Even as he praised the beauty of age in old buildings, he was sternly critical of any artist who made such effects the focus of their painting. This “picturesqueness” Ruskin attacked as “parasitical sublimity”, a sublimity “not inherent in the nature of the thing, but caused by something external to it.”5

7

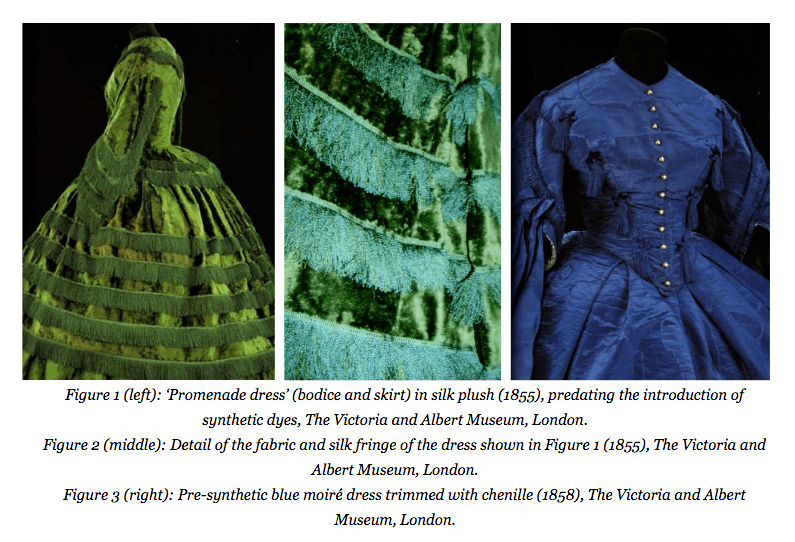

Images from essay Vettese Forster, S., Christie, R.M., (2013). The significance of the introduction of synthetic dyes in the mid 19th century on the democratisation of western fashion. JAIC Journal of the International Colour Association 11

Within fashion production the practice of artificially forged signs of age and wear and tear came to fruition most evidently halfway through the 19th century when synthetic textile dyes were invented:

These democratic changes were observed most significantly at a time coinciding with the discovery in 1856 of Mauveine, the first industrially-produced synthetic textile dye, and the consequent popularity of fashionable dress dyed in the mauve colour that this dye provided. Within a relatively short period of time, a range of so called aniline dyes had been discovered and introduced, providing access to a much wider range of bright colours for textiles. Newly created fashions in women’s wear, using the colours of these dyes, in various forms and of varying qualities, became more and more accessible to a wider population, and this led to the beginning of overlapping social class attitudes in the context of women’s fashion. […] The emergence of ‘democratic fashion’ was followed in time by a movement against the bright colours with which it was originally associated, in a movement akin to cyclical modern fashion trends. It was noted, for example in fashion magazines, that the synthetic brights had become popular in the dress of the lower classes and were used in garments of ‘inferior quality’. Godeys in 1872 stated, “Unmixed colours and all high colours, such as bright crimson, scarlet,clear blue and green have disappeared from choice goods and are only found in cheap materials made for the millions.” (…) The colours that became fashionable from around the late 1860’s were duller ones. It has been noted that ‘antique’ and ‘exotic’ effects were frequently sought after and the most desirable colours were described as ‘old-looking’, ‘strange’ or ‘indescribable tints’. Colours such as blacks, greys, ‘drabs’, ‘modes’ and unspecified browns and blues remained popular throughout that period.5

- Pye, Michael (2014). The Edge of the World. London: Penguin Books.

- Potter, Andrew (2012). Authenticity is a Con. Vestoj Issue 8.

- Veblen, Thorstein (2007). Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published in 1899.

- Haxthausen, W., Charles (2012). “Abstract with Memories”: Klee’s “Auratic” Pictures. Paul Klee: Philosophical Vision: From Nature to Art. Available here.

- Ibid.

- Vettese Forster, S., Christie, R.M (2013). The significance of the introduction of synthetic dyes in the mid 19th century on the democratisation of western fashion. JAIC Journal of the International Colour Association 11. Available here.